A week in Fiji

Tourists tend not to come to Suva, Fiji’s capital.

They should.

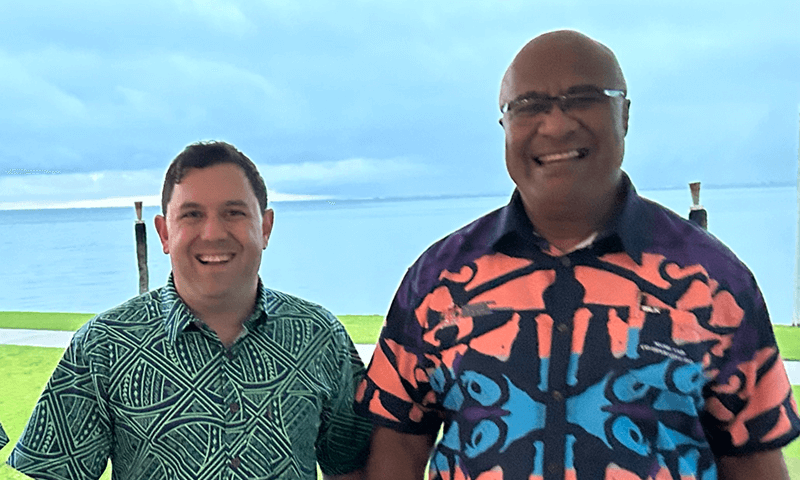

Cradled by a ridgeline of jagged mountain ranges and perched at the edge of a vast harbour, the city is as laden with natural beauty as any of the hundreds of tropical islands dotted around it. Bursts of tropical green are everywhere. Palm trees and bougainvillaea spring up in the Victorian-style Thurston Gardens but also in the disused construction sites in downtown Suva. The city buses have no windows. Passengers lean out and talk to people on the street as music blares out from the bus’s PA system. Fijians love their music, almost as much as they love their rugby. They’re good at it too. In the lobby of my hotel, a Fijian choir was singing what I think were Christian hymns. Their voices were so clear, their pitch so true, I might have been listening to the CD. I just spent most of last week in Suva and as you can probably tell, I miss the place already. I was there to talk with senior members of Fiji’s government and private sector about the country’s digital needs. Among the officials I met were Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Communications Manoa Kamikamica, the CEO of Telecom Fiji Charles Goundar and officials from the Ministry of Home Affairs and Communications. I also met with Sagufta Janif from Outsource Fiji, the peak body representing Fiji’s burgeoning BPO sector.

Jason Van der Schyff with Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Communications Manoa Kamikamica

That so many busy and important people were willing to give up their time speaks volumes about the generosity of Fijians. It also underscores the level of awareness inside the Fijian system about the scale of the challenge before it. Fiji’s corporate and political leadership understand the need to overhaul their digital economy and are willing to look to outsiders for advice on how to do it.

Like much of the Pacific, Fiji is in the midst of a vast digital transformation. For now, the priority seems to be internet and mobile connectivity. In Suva, coverage isn’t too bad but in regional parts of Fiji, things are patchy. Although most Fijians live in the capital, Fiji has more than 300 islands and connecting them is a major challenge. The small populations in some of these places mean there’s no private-sector case for putting in infrastructure. But the social value is obvious. When these smaller communities are wired into the rest of the country they can participate in the digital economy. More importantly, the government can roll out vital social services from telehealth to license applications.

At one level Fiji’s basic digital infrastructure is actually an advantage. Whereas more advanced economies like Australia and the US are in the process of transforming old analogue systems like driver’s licenses and payment systems to the net, Fiji is in a position to skip a generation and go straight to the newest tech.

But to do this Fiji needs robust infrastructure, not just 5G and another submarine cable. Most international development proposals emphasize traditional infrastructure like roads, airports, schools and hospitals, and rightly so. Fiji’s public health system is very basic. I was told there are no on-island chemotherapy treatments for cancer patients. Instead, cancer sufferers must fly abroad, usually to India, to receive treatment.

But it’s a mistake to see digital capabilities as a replacement for traditional infrastructure. They’re actually a force multiplier.

Reliable digital infrastructure can help facilitate the delivery of a greater range of government services, including health. Maybe not cancer treatments, but lower-order medical issues can be delivered via telehealth services, just as they are in parts of regional Australia where doctors and other health professionals are thin on the ground. Then there’s education.

It may not be ideal, but as the COVID-19 pandemic showed, it’s possible to educate a generation of school children with little more than an iPad and a few bars of 4G.

Of course, all of this will, and is, producing a mass of data. Storing that data is emerging as a major challenge. In developing economies like Fiji, private sector providers tend to be inclined to use the big hyperscalers, which are cheap and easy. But for governments data residency is the priority. The Fijian officials I spoke to made it pretty clear their preference was to keep Fijian data in Fiji. No surprise there.

The tension between the public and the private sector can only be resolved if Fiji can adopt scalable on-premises cloud products that can burst workloads into the public cloud at market-competitive prices. Again, the size of the Fijian market means that the big hyperscalers see no business case in setting up these kinds of capabilities in Fiji. The argument could be made for a kind of federated Pacific-wide service that uses the combined scale of the Pacific Island states to lure a Microsoft or an Amazon, but that’s a while off if it ever happens at all. For now, the Pacific Island states will need to look for other solutions.

As Fiji digitises and its stores of data increase it will become increasingly vulnerable to cyber attack. Indeed this is happening already.

Halfway into our trip, we hosted a Kava night at our hotel. With the lights of Suva harbour twinkling in the distance, we drank bowl after bowl of kava, clapping each time a new cup was delivered, as is the custom. One of the officials I spoke to said there had been a massive uptick in cyber attacks this year, mostly ransomware.

Fiji is also centre-stage in the great power rivalry playing out across the region, particularly the Pacific. This puts the country’s networks squarely in the firing line. None of this is news to Fijians. Without exception, every politician, public servant and executive we met recognised the need to overhaul Fiji’s digital platforms and to ring-fence them with robust security.

Nor were any of them under any illusions about the spectrum of challenges involved. Some are unique to Fiji, like the need to connect dozens of remote islands with expensive phone towers. Others are wearyingly familiar, like the difficulty in attracting and retaining skilled cyber workers. The Fiji government struggles to train or recruit cyber employees. And like governments everywhere it can’t compete with the private sector on salaries, making retention a constant challenge.

One area of the Fiji economy that seems to be doing well is the Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) sector. Sagufta told me that before the pandemic Fiji’s BPO sector employed around 2000 people. Now that figure stands at around 8000. BPO enterprises in big cities across the Philippines and India were hit hard by COVID-19 lockdowns. In Suva, which is smaller and less congested, employees could still make it work. Companies used Suva as a contingency capability, pivoting to call centres in Suva when the ones in Manilla or Bangalore had to shut down. And why wouldn’t they? Fiji has near-universal English and is situated in an adjacent time zone to Australia, New Zealand and Asia. Now that there’s a critical mass trained up workers Sagufta said the growth trajectory is expected to continue.

I’m sure she’s right, but just to be sure I think I’ll go back and check for myself. Moce.