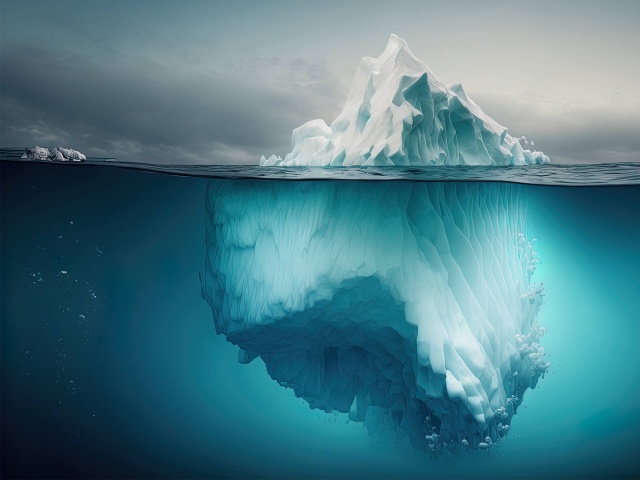

While repatriation of workloads from public cloud has been happening for years, we may now be entering a perfect storm where it will gather astonishing pace.

Last year, the “great resignation” was the trend that captured everyone’s attention. This year that has evolved into “quiet quitting”. But while these staff based responses to the shifts we’ve seen as a result of the pandemic, there’s a third primarily associated with data, not people, that has quietly been picking up pace and, with a number of factors now coming into alignment, the momentum it gains over the next few years could well shape the next phase of the IT industry.

Get ready for the Great Repatriation.

The pendulum at rest

The tech industry is full of pendulum swings. Over the last few years, we’ve seen the pendulum start to swing back from strategies that favoured moving everything away from owned IT infrastructure and into public cloud to a point of equilibrium around a hybrid cloud model – placing data and workloads in and across both.

Recent research reports the number of organisations now pursuing a hybrid model to be between 71% and 85%, with only 13% now pursuing a cloud-only model. In order to achieve rebalancing, it’s clear that workloads must move back from public cloud to an on-premise cloud service.

The most effective strategies, however, preserve the utility that makes public cloud so useful: its elasticity to accommodate unpredictable demand spikes, and its near-universal availability to maintain service quality and provide backup and disaster recovery where necessary.

Why repatriate?

Data and workload repatriation is happening for one (or more) of a number of reasons:

Cost

The way public cloud providers charge for their service makes it cheap to place data in the cloud, but expensive to get your data back out. These so called egress fees can soon mount up if left unchecked, and with the disaggregated way in which cloud is often purchased on the credit cards of a dozen different departments, it’s easy to lose control of these costs really quickly. In many instances, the costs of these egress fees can be compounded further because of the nature of the application that is driving them. If the application wasn’t designed to be “cloud first” – and must pull data back from the cloud in order to process it every time, then there’s no getting away from these costs unless you bring the data back on-premise (note: arguably you could move the app to the cloud as well as the data to avoid the egress fees, but there are many instances where this just isn’t technically feasible or desirable – especially if the app is being supplied by a third party).

Data sovereignty

Concerns over data privacy, regulatory compliance, and/or national security are becoming increasingly critical in multiple global marketplaces, compelling many private and public sector organisations to reconsider where they store their data. Public cloud vendors have started to respond, striking up deals with local (often national telco) service providers to build and operate infrastructure locally in their name. These so called “Sovereign Clouds” primarily seek to address concerns over data privacy by using local third party oversight, though under the hood, it is the same architecture as used in any other location and the underpinning software and hardware remain obfuscated from those with that oversight and those that place their services upon it.

For many, this approach to providing data sovereignty provides scant assurance that their data is in any better position than in more generic cloud offerings.

Performance

As more data is generated at the edge of our networks from initiatives such as IoT and AI, and the value of the decisions made from processing that data has an ever shorter half-life, the sheer physics of doing this in the public cloud becomes harder and harder to achieve. The remedy is to place local instances of cloud service physically on-premise to where the data is being generated and must be processed. A couple of the public cloud providers will put a rack of managed hardware of their cloud in your data centre to achieve this, but for many organisations, the trade off of lock-in to that specific provider, plus the ongoing fees associated with that service, prove to be a step too far.

So, what’s the catch?

Bringing your data back in-house is all well and good, but there were good reasons you went to the public cloud in the first place. Included there was the speed with which new services could be spun up, the elimination of the overhead of looking after infrastructure and the shift to a third party for guaranteed and secure service availability – all delivered with a substantial cost saving. The reality for many, though, is that it is not the way things have completely turned out.

While the promise of huge cost savings may not have materialised in the way you had imagined, the world has changed between now and then.

If your cloud repatriation project is going to be successful therefore there will be a few hurdles that must be crossed:

User experience

Your applications owners have become very accustomed to the cloud experience with the immediacy and utility that it provides at their fingertips. It’s an experience you’ll want to replicate or those departmental credit cards will be flexed once more and the developers will walk straight back to the public cloud.

Complexity and an IT skills shortage

It’s very possible in many organisations that, in the rush to a cloud first strategy, the quality and/ or quantity of in-house IT infrastructure skills may have diminished. Traditional methods for constructing a private cloud are incredibly complex to both deploy and maintain. In a world where IT skills are in short supply and are at a premium, doing things the old way may not be practical, desirable or even possible.

Keep costs down and sustainability high

And it’s not just the salaries of the highly paid engineers that have the potential to drive up cost. Repatriating data will require equipment and real estate to house it. It will require power and cooling to operate it. All this while at the same time IT organisations are being put under pressure to report and reduce their carbon footprint to support broader Net Zero targets.

Yet with all these challenges, repatriation projects continue apace. In fact, the ingredients may be in place, and the timing may now be right for the pace of repatriation to substantially accelerate.

A perfect storm to accelerate repatriation

If there were compelling reasons for repatriation before, I’d argue that the drivers and enablers today create a perfect storm for that snowball to accelerate – and dramatically.

A global recession

While not universally declared as such, there’s no doubt that economies around the world are seeing a marked slowdown. In such times, cost control comes under much greater scrutiny. Those egress costs might have slipped under the radar before, but not now.

Global shift to sovereignty

With projects underway in numerous regions of Europe, Asia and Australia, the desire to bring data back under sovereign control has never been greater.

Edge projects accelerate

Every projection for edge computing, and the resulting low latency and high performance that it demands, forecasts a shift from pilot projects to increasingly mainstream deployment in 2023 and beyond.

Net zero initiatives start to bite

IT comes under the microscope to deliver its contribution to a lower carbon future.

HyperCloud becomes available

And lastly, of course, the enabling technology that enables highly energy efficient, cost effective, performant cloud infrastructure to be built – a highly integrated and automated infrastructure that requires only IT generalist skills to deploy and own, has come to market. HyperCloud changes the accessibility and economics of building scalable, resilient and secure clouds forever.

HyperCloud unlocks the “Great Repatriation” just at a moment in time when it is sorely needed.

Find out more about HyperCloud.

Read about IDC’s view on this topic here.